Retro computing with a touch of modern and the home for all things, retroCombs (aka Steven Combs).

Disclosure Statement: When you click on links to various merchants on this site and make a purchase, this can result in this site earning a commission. Affiliate programs and affiliations include, but are not limited to Amazon, the eBay Partner Network, and/or others.

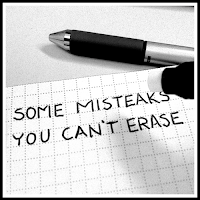

Make mistakes, learn from them, and own them

by Steven B. Combs, Ph.D.

Yesterday I began a series of lessons learned from my first year as a Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs (VCAA). Today I share lesson number two – mistakes.I’ll admit that our college does not have a robust training program for new VCAAs. My training program was a two day orientation with four other “newer” regional VCAAs. The sessions was beneficial, but as our moderator explained, that training would not prepare us for our new roles. We would make mistakes. He was correct, but that session did prove valuable. It gave me a cohort to share ideas.

Yesterday I began a series of lessons learned from my first year as a Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs (VCAA). Today I share lesson number two – mistakes.I’ll admit that our college does not have a robust training program for new VCAAs. My training program was a two day orientation with four other “newer” regional VCAAs. The sessions was beneficial, but as our moderator explained, that training would not prepare us for our new roles. We would make mistakes. He was correct, but that session did prove valuable. It gave me a cohort to share ideas.

The one thing I had that my new peers did not was my previous experience within the college – over twenty years. I’ve served at two other regional campuses and on numerous statewide committees. I was around when the college made the transition from vocational college to a comprehensive community college. I was one of the first to implement online education within a region.

These experiences provide me with a large pool of colleagues, who also have many years of experience, to tap into. Many of them have even held the position of VCAA. It is easy for me to contact any one of them and ask for their advice, coaching and/or mentoring. Surely this large base of knowledge will keep me from making mistakes…right? The answer is of course “no” as you will discover after hitting the link below.

Despite the resources available to me, I made a mistake early on that affected my professional relationship with a couple of individuals. I won’t go into specifics here, but suffice it to say that we are not always given the opportunity to sit back and observe before we make changes. Leadership articles often suggest this is good practice – in theory; however, sometimes external forces, such as budget and institutional priorities, don’t allow it. I spent 27 years in the military, I was trained to make quick decisions and live with the results of those decisions. But the military also teaches its leaders to learn and manage from their mistakes.

Anyone new to any position will make mistakes. What you cannot do is dwell on the mistakes. You made the decision, you made the mistake, and you may be able to correct it. Correction may involve a simple reversal of a decision or action. Another option may be to make another decision that lessens the effects of the first. If neither of these are an option, then you must live with the mistake.

No matter what action you take to lessen a mistake, you must learn from it. You learn by self-reflection (I journal and blog). While you review your mistake, try and understand the:

- process used to formulate the decision.

- current implications of your decision.

- future implications of your decision.

These can be some tough nuts to crack; however, taking the time to sit back and analyze your mistake will stop you from quickly making the same mistake again and may even better prepare you to not make a different and/or similar mistake down the road.

##“Here’s the real lesson…ADMIT your mistake!

Want to grow in your professional maturity? ADMIT your mistake! No, “ifs,” “ands” or “buts” about it. Integrity is key to your long term viability as a leader and decision maker. Integrity will ensure that your mistake does not back you into a professional corner. If you try and cover a mistake, you will do even more harm to the situation and potentially your career. You will also lose the trust of your supervisor, peers and subordinates. They will not trust a decision maker who cannot own up to their own mistakes or who refuses to learn from them.

Did you notice my mention of subordinates? You need to admit your mistakes not only to your superiors, but also your subordinates. You must do this in a way where you take complete responsibility. Do not throw someone else under the bus. I’ve seen this tactic used too many times. It begins with, “Yes, I made the mistake, but…” and that’s a “but” usually followed by blame of someone else. It doesn’t matter who was involved. As a leader, you have responsibility for your own mistake. Simply own the mistake and move on. You will be amazed at the level of respect you gain.

Anyone have anything to add to this lesson? I’m not asking for specific instances, although those would probably prove interesting, but why not share your tips and tricks and share how you deal with mistakes. You can do this in the comments section below.